Your cart is currently empty!

10 Jul SAILOR JERRY – FROM PIONEER OF THE TRADITIONAL TO INFLUENCE THE NEOTRADITOIONAL

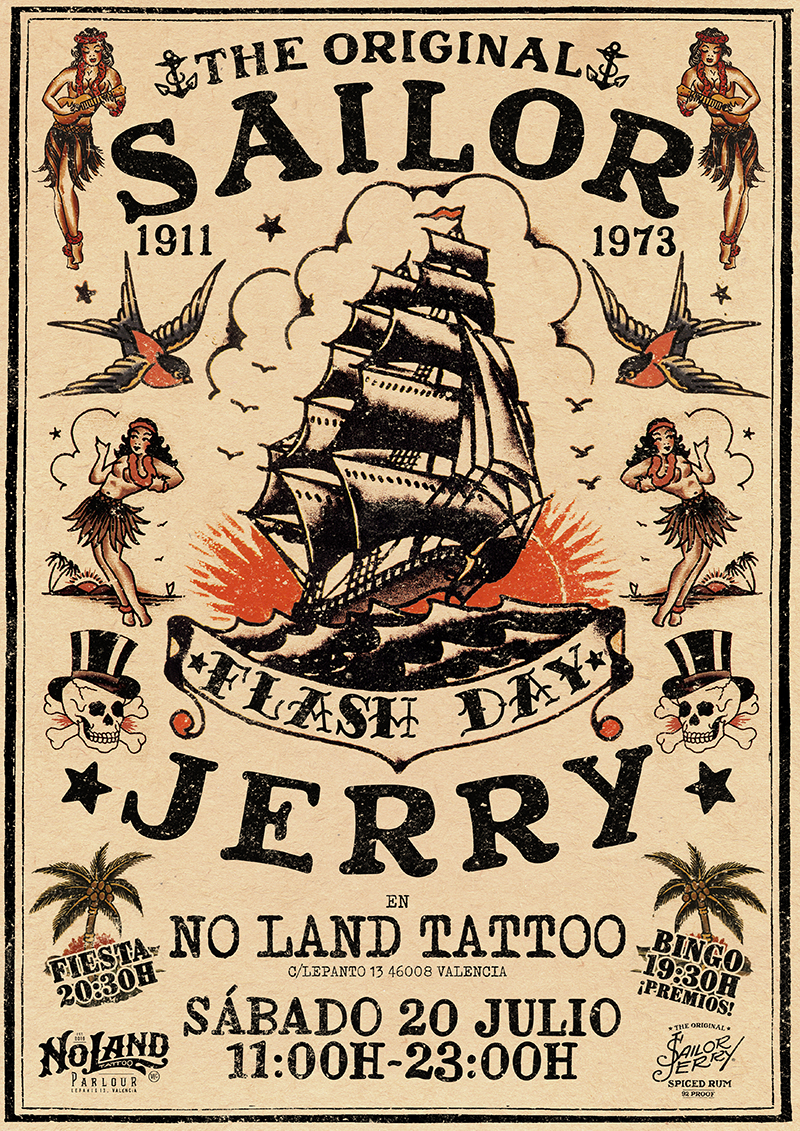

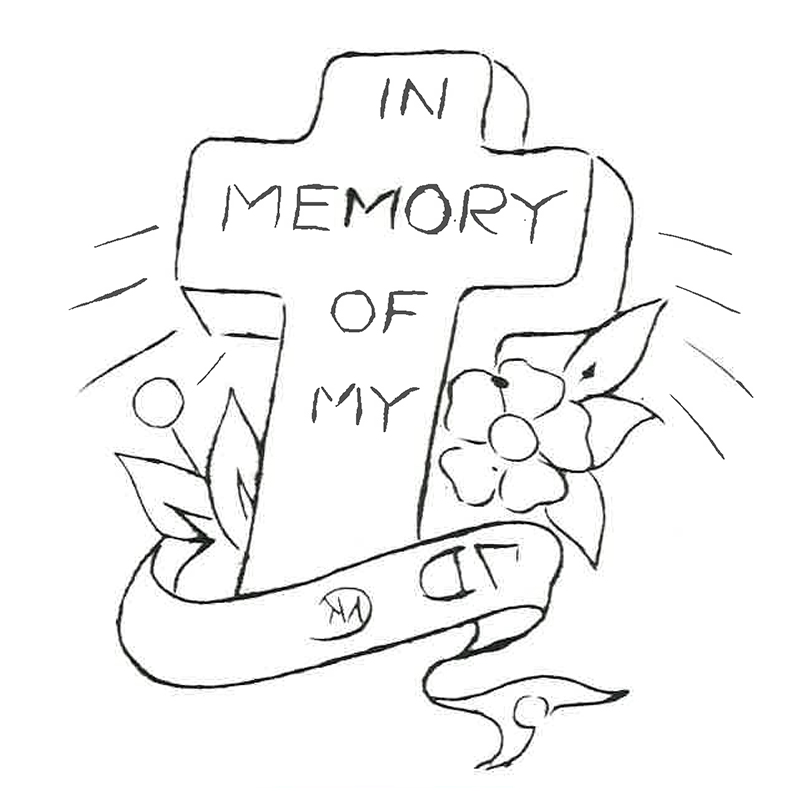

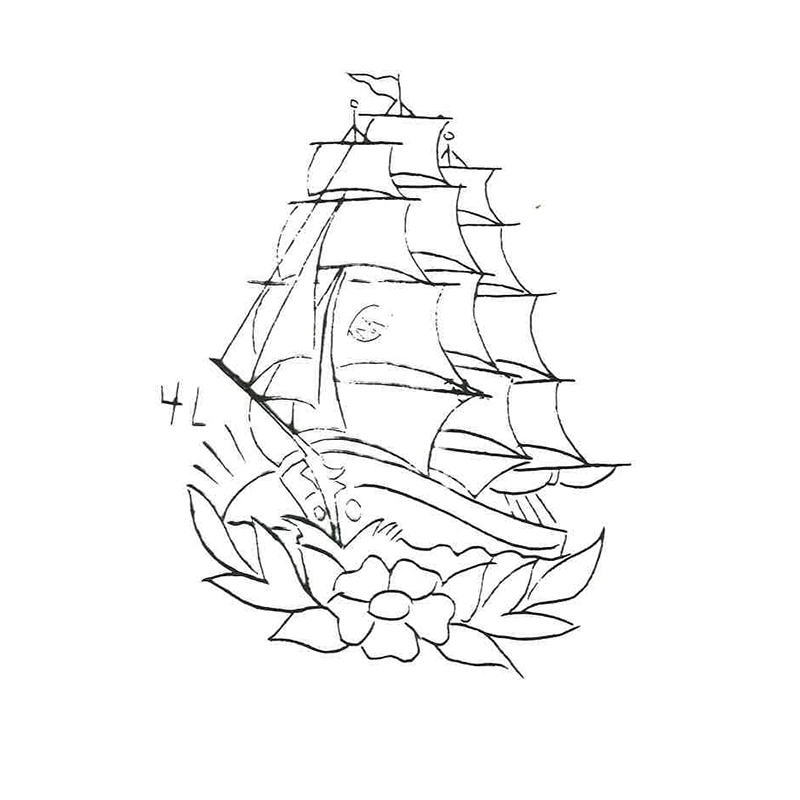

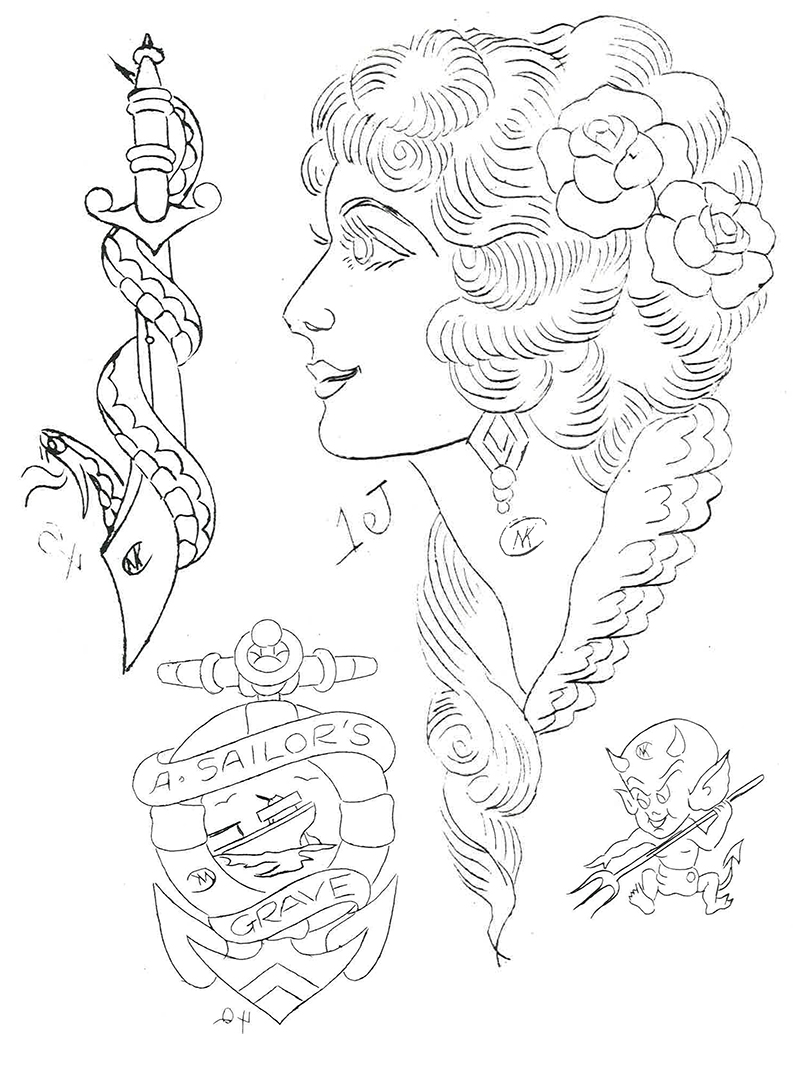

On Saturday July 20th we celebrate a very special Flash Day in commemoration of the 46th anniversary of the death of tattoo master Sailor Jerry (14/01/1911- 12/06/1973). During this special day we will present a few designs of the mythical tattooist at reduced prices that will be tattooed during the morning and afternoon, to conclude the day with a party in which there will be DJs, Ron Sailor Jerry and a summer Bingo in the purest Benidorm style with numerous gifts related to the American artist (pins, embroidered patches, bottle opener, metal plates to hang on the wall, …). The tattooing schedule will be from 11 a.m. To 11 p.m., and we will start the party with Bingo at 7:30 p.m. Live music will start at 8:30 p.m. until the end of the event. We will present more than 50 designs that can be made in color or in black and gray. These designs may be repeated and the price will be per design. They will not be tattooed on ribs or stomach. Tattoos can be made by appointment or without it.

The designs will be shared on our social media network on July 13 (Facebook / Instagram) ,and to make an appointment you will have to come the studio to leave a deposit and choose the design.

More information on the Facebook event: Pincha aquí

Here is some very interesting information about the work and influence of Sailor Jerry on the world of tattooing.

SAILOR JERRY

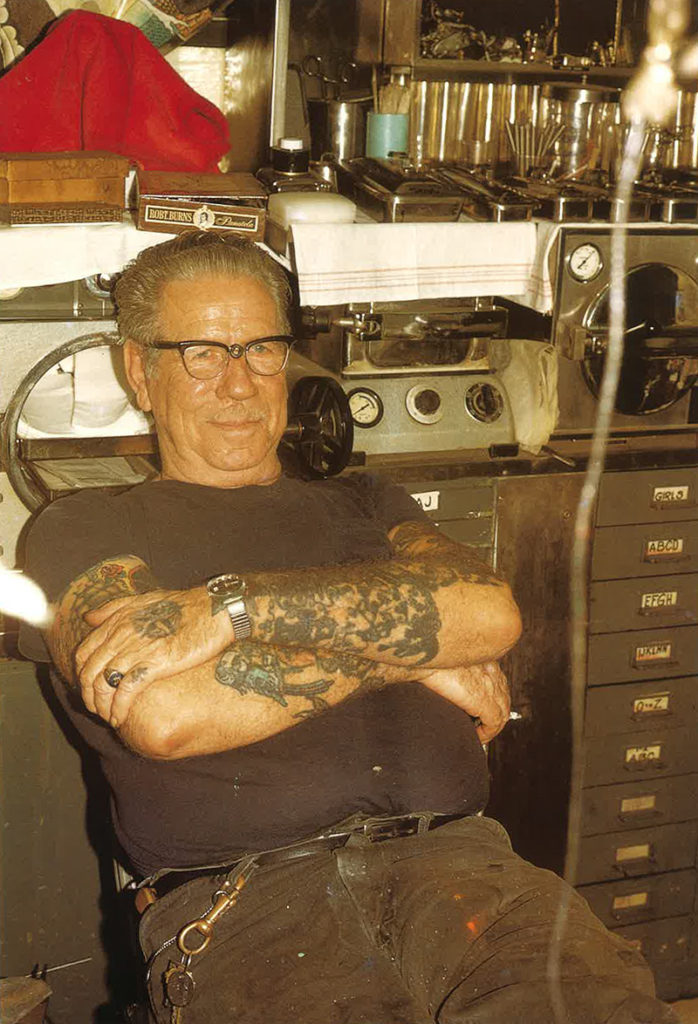

Norman Keith Collins, better known as Sailor Jerry was an innovator who transformed the art of tattooing, and whose influence was incredible on every aspect of this mixture of art and science called tattooing that precedes the first records of history. He was born on January 14, 1911 in Reno (United States) but grew up in California. When he was very young, he traveled all over the country as a stowaway on trains, and learned to tattoo himself with a guy named “Big Mike” using the “Hand-poke” method until Tatts Thomas (Chicago tattooist) taught him to use a tattoo machine with which he practiced on drunks from Skid Row, a poor neighborhood in Los Angeles.

At the same time that he was starting to learn how to tattoo, he joined the U.S. Navy in 1930, and, before settling in Hawaii, he sailed the Pacific Ocean, where he immersed himself in the art and iconography of Southeast Asia.

REDEFINING AN ANCESTRAL ART

Sailor Jerry Collins has been called the American Tattoo Master and his influence in the world of tattooing cannot be measured. From 1936 until his death in 1973, Collins was relentless in his crusade to elevate tattoos in every possible way. There’s not one aspect Jerry hasn’t revolutionized. His inventions and renewals covered everything from hygiene and health problems to discoveries of new pigments.

His intellect served to influence the tools of the trade, fine-tuning the power supplies and the machines themselves. He invented new needle configurations that introduced ink into the skin without trauma. He became one of the first artists to use single-use needles and one of the first to use an autoclave to sterilize equipment in his tattoo studio. He also fiercely and unapologetically defended a philosophy that viewed tattoo artists as shamans of recent times.

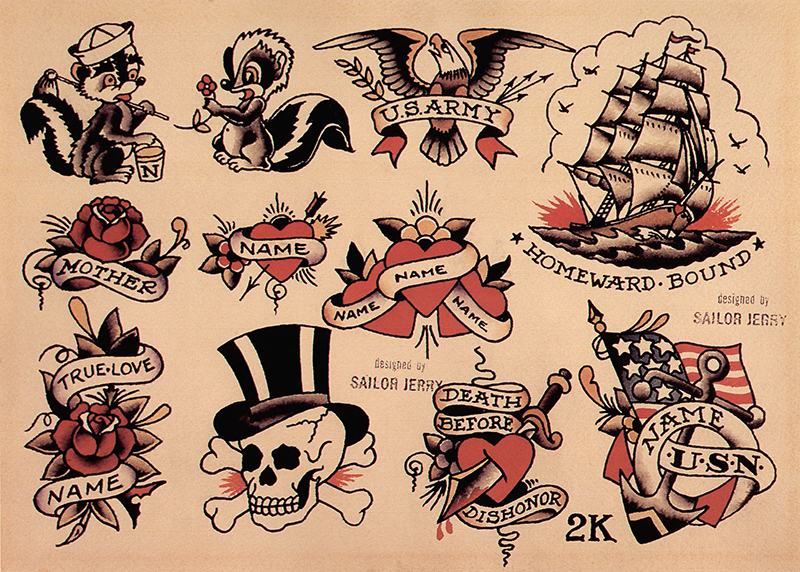

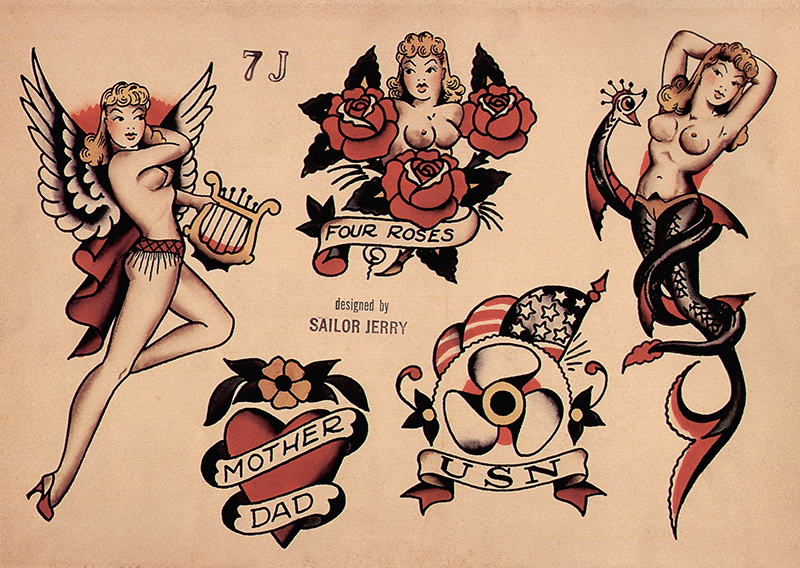

Probably Jerry’s most notable contributions were his tattoo designs. Before Jerry’s chubby, sensual style tattoos were primitive, thin, and rough. Jerry’s vision was a composition of strong, thick lines, relentless black shading, and the introduction of his new pigment discoveries. This way of seeing the tattoo allowed everything to flourish under his personal touch. His strongest legacy, however, would be his “Cheesecake Pinups”. He is the Vargas, the Elvgren, the Frazetta of pinup tattoo designs. He created dream girls with long legs and wasp waist, typical of the beauty canons of the time, unmatched then and now.

Jerry’s greatest hope was that his beloved world of tattoos would be taken seriously, and he tried to set a new, higher standard for his art. So far only a small part of his work has been in museums or galleries, and his flashes can be found in exhibitions of popular self-taught artists.

His hand-drawn flashes are a summary of the classic Euro-American tattoo of the mid-twentieth century. He embodies the strength and security reflected both in his tattoos and in his lifestyle. Working his entire career with the early seafaring communities, Collins inherited a delicately developed graphic language that was shared and scrupulously transmitted by other practitioners of the ancient craft. A tattooist’s flashes were the key to his success, often eclipsing his real experience in the epidermis. The worn sheets were what sold the tattoo, and studios competed to show strong, varied and striking flashes. Often these sheets on the walls weren’t even the work of resident artists, and perhaps were left behind by the transient occupants of that space, commissioned from known talents in the business or ordered by tattoo supply houses.

Most of Jerry’s career was spent in the Chinatown of Honolulu, the main honkytonk district for sailors, where he occupied a large number of small shops. The final location, where he tattooed from 1960 until his death, was only 2.70 by 5.50 meters. Working in such small places required putting in each flash as many designs as possible. During Jerry’s career, tattoo parlors on Oahu Island could only be found in Chinatown. A variety of shops thrived there, especially during World War II.

Generally, each had a squadron of operators, all looking for money. Sailor Jerry’s competitive strategy was to offer customers the best possible tattoo with the widest variety of colors and designs. The style he defended became an American tradition developed by artists such as Charlie Barrs, “Cap” Coleman, Amund Dietzel, Owen Jensen, Harry Lawson, “Brooklyn” Joe Lieber, and Paul Rogers. Both the work on the skin and on paper emphasized the thick contours, the intense shading, the elegance, the clarity, and the absolute sharpness of the execution. The intention was to create tattoos that would age gracefully and keep their integrity for life. The flash too was made to last. Jerry was very scrupulous in using only the best quality materials to ensure that his paper art would endure. This happened at a time when the trends in tattoo designs changed very slowly, so a good set of flashes could be useful for many decades.

As with all traditional flashes, the designs were a combination of images he originated, adapted from external sources (newspaper illustrations, cartoons, etc.), or exchanged with other tattooists. The practice of exchanging handmade acetate templates that accompanied each sheet of flash created a common design group among tattooists around the world. Most tattooers lacked freehand skill and relied on the drawings of their craft, first with the designs painted on the flash, then tracing the charcoal template on the skin. Tattooists who left the shop employment used to secretly pocket as many designs as possible from the template archives. These could then be repainted, redeemed or used as an influence to obtain a job in another studio or city. As good flash was the main stock of a shop in business, flashes and templates were tightly protected; popular designs to make money and new variants that appeal to people who wear tattoos and who look for them eagerly. To avenge this type of theft, Jerry often purposely cut the templates imprecisely of some of his key images and thought that any tattooist without eyes to correct the drawing deserved a crooked job. Of course, any potential recipient of the sabotaged image was the one who bore the consequences of this internal struggle.

Ironically, the use of these traditional images generally declined during the early years of the “tattoo renaissance” (1970s and 80s), but they gained a new popularity in the early 1990s and were among the most striking styles of international professional tattooing. Then they declined again in favor of the custom tattoo, which grants an original design to each client according to their preferences, and are now back on the agenda with the rise of the traditional tattoo among the younger generations.

The race towards increasingly complex techniques and visual images that drove the tattoo trend and that in recent years has begun to give way to a renewed appreciation for tradition. From faithfully re-interpreting the master’s designs to evolving to different levels of the neo-traditional, or also called neotradi, in which the bases are still hard lines and a good contrast of black, but the artistic level is much higher, many more details are included, sometimes even bordering on realism. It could be said that today 70% of old school, neo-traditional or even blackwork tattoos come from the time of sailor Jerry and his contemporaries, whether the tattoo artists who make them know it or not, since certain designs have been reinterpreted so many times and tattoo artists have been influenced by other tattoo artists, that we literally lose track of where the original idea came from.

Realistically, the nuances Jerry valued would escape the eye of the tattooist. This was a good thing to systematize rules and regulations of a good design as he was a fan of the right and wrong way to draw, shadow, and color each design. Although partially based on experience (his own and that of others he admired in the business), these formal stylistic imperatives were reduced to a matter of taste: the ineffable aesthetic preference that attracts to or repels any form of art or design. For Jerry, the shape of an eagle’s wing or the method of shading a rose were matters of almost religious importance. This fierce conviction, combined with his masterful hand and unwavering determination, created the magnetic force of these drawings that almost 100 years later is still there and will continue to inspire tattoos all over the world.

We are very grateful to you, Norman!